The WWII-Era Heroics of the Real-Life Monuments Men

During World War II, a group of unlikely heroes emerged who were dedicated to preserving the world’s cultural heritage. Known as the “Monuments Men,” this team of art historians, curators and conservators risked their lives to safeguard masterpieces from destruction and theft by the Germans. Delve into the captivating story of the real-life Monuments Men and how they deviated from their on-screen Hollywood representation.

The Monuments Men (2014)

The Monuments Men (2014), starring George Clooney, Bill Murray, Matt Damon and John Goodman, brings a very different war story to the silver screen. Unlike other popular movies in the genre, it doesn’t focus on intense battles, but, rather, on what a very specific group of Americans did behind the lines in enemy territory during the final years of WWII.

The film is based on a 2007 non-fiction book by Robert M. Edsel and Bret Witter, which discusses the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives program (MFAAP). This was a very real group, with many of the film’s characters loosely based on real-life members.

The story is generally considered to be historically accurate, with Clooney himself telling Entertainment Weekly, “[Eighty] percent of the story is still completely true and accurate, and almost all of the scenes happened,” even if they received some Hollywood flair.

Despite this, The Monuments Men received horrible reviews upon its release. It currently holds a rating of 31 percent on Rotten Tomatoes, with one critic writing, “I respect the inspiring story being told, but the film’s screenplay doesn’t have the necessary weight in its pages, or the depth in its characters.”

‘Roberts Commission’

The MFAAP was part of the larger American Commission for the Protection and Salvage of Artistic and Historic Monuments in War Areas. The program was initially founded as a group to try and preserve historic buildings throughout Europe, not protect artwork.

The plan, according to historian Elizabeth Campbell Karlsgodt, was to “provide lists so that Allied forces wouldn’t bomb historic sites, and once they were on the ground, then identifying damaged buildings and trying to carry out repairs when they could.”

Called the “Roberts Commission” after its chair, the group set about drafting lists of cultural items at their headquarters in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. These were subsequently passed on to military units serving overseas.

Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives program (MFAAP)

With lists in hand, the hope was that they could help protect these monuments. However, the commission went one step further when it founded the MFAAP within the Civil Affairs and Military Government Sections of the Allied armies. This was made up of 345 men and women of various nationalities who became the boots on the ground for historical preservation overseas.

The MFAAP was made up of a hodgepodge group of artists, historians, museum directors, curators, architects and professors tasked with assisting in the protection of historic sites outlined by the Roberts Commission by trying to dissuade bombing of these areas.

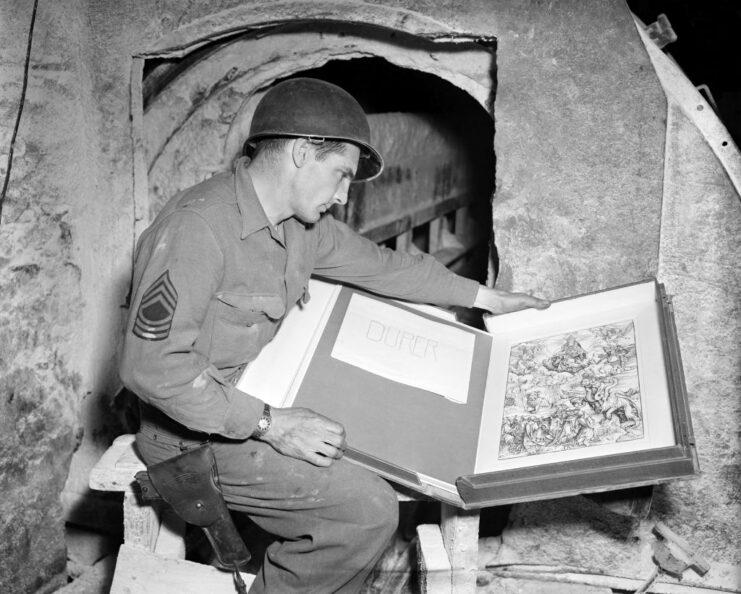

What they’re best known for is, of course, their work in recovering looted art and artifacts from German-held locations and trying to get them back to their rightful owners. In 1945, they began seeking 1,000 treasure troves, which included paintings and statues taken from museums, churches, universities and private collectors.

Part of this required MFAAP officers to be on the frontlines alongside normal soldiers, as they were typically attached to Allied units, despite receiving little training. Their work was without precedent, so there were simply no handbooks and little guidance on what they were supposed to do.

Monuments Men served on the frontlines

The Monuments Men didn’t hide out until the fighting was over. Under the Operations Branch of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF), Europe, they contributed in many ways. During the planning stage to take Florence, Italy, for instance, the Allies were provided with aerial photos taken by the MFAAP.

Often, the Monuments Men were some of the first to enter a liberated town, as they cataloged the damage to cultural sites. Of course, work like this was incredibly dangerous. They often found themselves in life-threatening situations, and there were two recorded deaths among their officers: Capt. Walter J. Huchthausen and Maj. Ronald Edmond Balfour.

The former, an American architect and academic attached to the US Ninth Army, was killed during a shootout in Germany in April 1945. The latter was a British historian attached to the First Canadian Army, who was killed on a mission to find stolen artwork near Kleve, Germany in March 1945.

Altaussee salt mine

The central plot of The Monuments Men focuses on their mission to try and find the Madonna of Bruges. They locate it inside the Altaussee salt mine, just as the men did in real life. In fact, the mine served as one of the largest repositories for art stolen during the war. Much of what the Germans hid there was intended for use in the Führermuseum, which they planned to build in Austria. It was an ideal hiding place, as it was an extensive underground complex that was difficult to navigate.

The US Army arrived in the region in May 1945, accompanied by MFAAP officers. They seized the art depot and were able to recover not only the Madonna of Bruges, but other famous pieces, including the Ghent Altarpiece, The Astronomer, The Art of Painting and various paintings from Italy’s Capodimonte Museum that had been stolen during the fighting at Monte Cassino. Contained in the mine were roughly 6,500 paintings, as well as weapons, books, coins and statues.

Notable finds by the Monuments Men

While the Altaussee salt mine contained many famous works, it wasn’t the only location that did.

To say the Monuments Men found some of the most illustrious art in Europe would be a gross understatement. By the end of their search, they’d returned well over 10,000 pieces, including non-art items of historical value. These included coffins containing the remains of Frederick the Great and Field Marshal Paul Von Hindenburg, along with a number of other notable German leaders.

The 101st Airborne Division identified a repository in Berchtesgaden, Germany that contained 1,000 pieces the Reichsmarschall had personally taken. At Neuschwanstein Castle, over 6,000 were found that had been looted from private art collectors.

Supposedly, there are still tens of thousands of art pieces still unaccounted for to this day. Among those still missing are Sandro Botticelli’s Portrait of a Man and Bernardo Bellotto’s View of the Grand Canal in Venice. Nonetheless, that number pales in comparison to how many artifacts the Monuments Men recovered: roughly five million.

Post-World War II activities

While most of the work conducted by the MFAAP occurred in Europe, a new division was created in Japan as the war drew to a close. Just because the conflict ended didn’t mean the work was done, either. The team shrunk, but there were still 60 members working throughout Europe some six years after V-E Day.

The others returned to their day jobs, where they became influential members of the art and museum communities. Those who weren’t already professors before their wartime escapades often went on to teach at some of the most respected universities in their respective countries.

More from us: Witold Pilecki Risked His Life for the Polish Resistance By Voluntarily Being Imprisoned at Auschwitz

While the Monuments Men’s investigations are long over, we shouldn’t give up hope that some of these missing items may still turn up. In fact, in November 2013, between 1,400 and 1,500 pieces were found in the apartment of a Munch art dealer who’d been in business during the war.

The post The WWII-Era Heroics of the Real-Life Monuments Men appeared first on warhistoryonline.

The WWII-Era Heroics of the Real-Life Monuments Men

Philippines Truth

Post a Comment

0 Comments