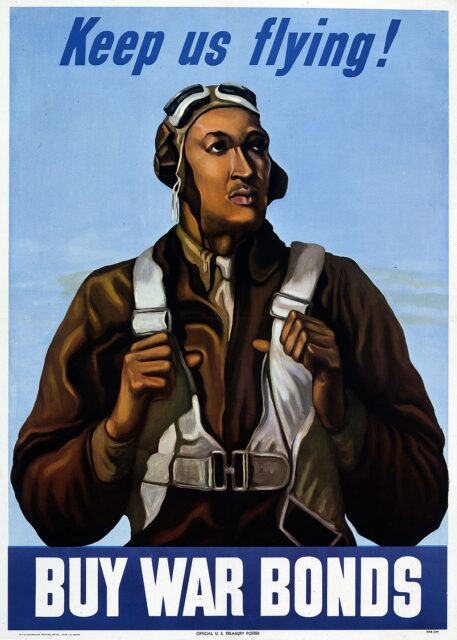

Tuskegee Airmen: The African-American Pilots Who Broke Barriers in World War II

In the early 20th century, the notion of African Americans serving as pilots in the US military was unthinkable to many in power. However, as World War II loomed, the pressing need for skilled aviators led to a significant policy change. With the outbreak of the conflict, the US Army Air Corps (USAAC) established the 99th Flying Training Squadron, with the graduates going on to form the Tuskegee Airmen.

Reconsidering racial segregation in the US military

The US government, under pressure from civil rights organizations and the Black press, began reconsidering its stance on racial segregation within the military prior to the Second World War. African Americans hadn’t been given the opportunity to serve as pilots before the conflict, thanks to the country’s racist Jim Crow laws. As well, a 1920s War Department report had stated Black Americans weren’t smart or disciplined enough to pilot aircraft.

As a result, many African Americans who longed to take to the skies served under other countries during the First World War – most notably, Eugene Bullard, who traveled to France to fight with America’s allies.

The push for integration within military aviation was led by the likes of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), civil rights leaders and prominent Black media outlets. They argued that African Americans should be given the very same opportunities as their White counterparts to serve their country.

This advocacy culminated in the establishment of pilot training programs for African Americans, first in the civilian sector, then within the military. However, this occurred differently to how advocates had envisioned, as they were segregated groups, rather than serving alongside their White counterparts.

Creation of the Tuskegee Airmen

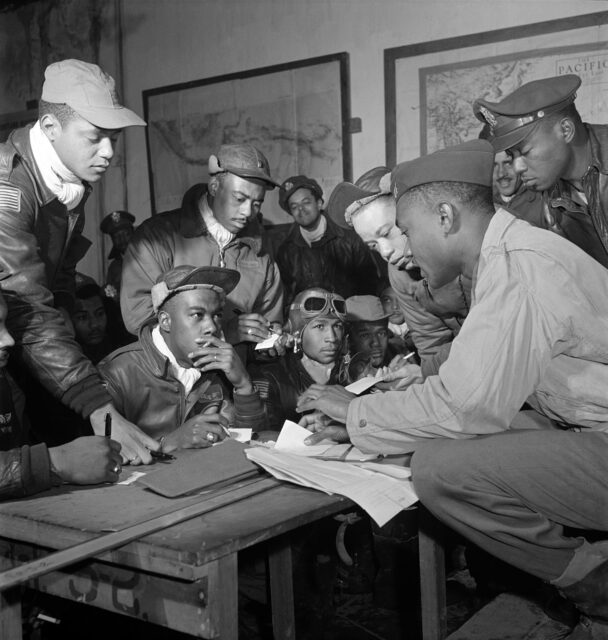

The 66th Air Force Flying School, at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, became the training ground for African-American pilots. The training program was rigorous and, early on, designed for them to fail. It wasn’t until First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt visited in March 1941 that things began to change.

The cadets were trained to meet the challenges they’d face in combat. This included not only flight training, but also instruction in navigation, meteorology and aircraft maintenance. The curriculum was comprehensive, ensuring they were equipped to handle all situations they’d possibly encounter.

The first class began their training in 1941. The initial group of Tuskegee Airmen consisted of 13 trainees, a small but determined cohort who paved the way for future generations of African-American pilots. The program later expanded to train pilots to fly the North American B-25 Mitchell, who’d make up the 477th Bombardment Group, but they never were deployed overseas.

By the end of the Second World War, around 1,000 Black aviators had trained at Tuskegee, along with 14,000 bombardiers, navigators, aircraft mechanics and maintenance crews, control tower operators and support staff.

Serving overseas during World War II

The Tuskegee Airmen were assigned to the 99th Pursuit (later Fighter) Squadron, Twelfth Air Force, and initially stationed in French Morocco, in North Africa, where they joined the Allies in the fight against the Axis forces. They subsequently served in Tunisia, Sicily and Italy.

With the Twelfth, they flew hundreds of missions in secondhand Bell P-39 Airacobras and Curtiss P-40 Warhawks. Their first combat mission occurred in 1943, when they were tasked with attacking enemy positions on Pantelleria, Italy. It was a success, setting the stage for future engagements in the European Theater.

Before long, more squadrons (the 100th, 301st and 302nd) had arrived to form the 332nd Fighter Group.

The Tuskegee Airmen gained a reputation for their skills and bravery in combat. They were reassigned to the Fifteenth Air Force and charged with escorting Consolidated B-24 Liberators and Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress deep within enemy territory. For these operations, they piloted Republic P-47 Thunderbolts and North American P-51 Mustangs.

Their success in protecting bombers from enemy fighters was unmatched, and the pilots were credited with significantly reducing losses during their over 15,000 sorties across nearly 1,600 missions. Their red-tailed aircraft became a symbol of their aerial skill, earning them the nickname, “Red Tails.”

One of their most noteworthy missions took place on March 24, 1945. While flying to Berlin, Germany, the Tuskegee Airmen destroyed three Messerschmitt Me 262s and damaged another five fighters, leading to them receiving a Distinguished Unit Citation. Their last mission occurred on April 26, 1945, with them having one of the lowest loss records of any escort group.

How did the Tuskegee Airmen handle racism within the US military?

Despite their successes, the Tuskegee Airmen faced significant challenges, due to pervasive racism within the military and society at large. They were often subjected to discrimination and prejudice from their White peers, which manifested in many ways, from hostility by others to being denied access to certain facilities.

The airmen’s response to this racism was one of resilience and determination. They remained focused on their missions and continued to excel in their roles, proving their worth through their actions and achievements.

What happened to the Tuskegee Airmen in the post-war era?

Following the end of World War II, the Tuskegee Airmen returned home to a country still grappling with racial inequality. Despite their significant contributions to the war effort, they continued to face discrimination and prejudice.

Many went on to have successful careers in various fields, using their experiences and skills to effect change and advocate for civil rights. They became leaders and role models, demonstrating the potential for African Americans to excel in every area of society.

Thanks, in part, to their wartime service and that of other Black units (over 1.2 million African Americans served in the conflict), the US military desegregated in 1948, after which their experience became highly sought-after.

An enduring legacy

The Tuskegee Airmen’s legacy continues to be celebrated and honored today. Their achievements have been recognized through various awards and honors, including the Congressional Gold Medal in 2007. Alongside three Distinguished Unit Citations, the aviators also received 14 Bronze Stars, 96 Distinguished Flying Crosses and eight Purple Hearts for their service in World War II.

Their story has been immortalized through the preservation of the airfield where they trained, which today is known as the Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site. Their exploits have also been brought to newer generations through the release of various forms of media. In 1995, HBO released The Tuskegee Airmen, while George Lucas helped produce Red Tails (2012).

More from us: Why Did John F. Kennedy Keep a Coconut in the Oval Office?

Want War History Online‘s content sent directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter here!

On top of this, the 99th Flying Training Squadron remains active, flying red-tailed Raytheon T-1A Jayhawks, in honor of those who came before them.

The post Tuskegee Airmen: The African-American Pilots Who Broke Barriers in World War II appeared first on warhistoryonline.

Tuskegee Airmen: The African-American Pilots Who Broke Barriers in World War II

Philippines Truth

Post a Comment

0 Comments